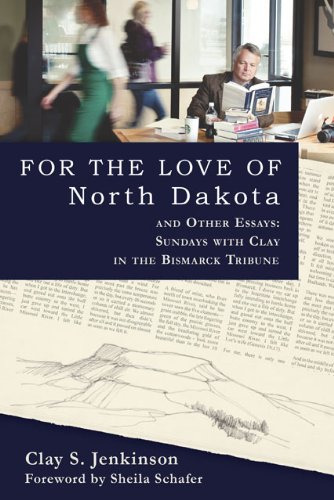

For the Love of North Dakota and Other Essays: Sundays With Clay in the Bismarck Tribune.

By Clay Jenkinson. (Washburn, North Dakota: The Dakota Institute Press, 2012) 364 pages. A review by Aaron L. Barth.

When writers describe a place, they explain their surroundings while they intentionally or inadvertently explain themselves. Clay Jenkinson’s For the Love of North Dakota is a sounding board for this, as a collection of his Bismarck Tribune essays are now accessible from The Dakota Institute Press, this from the northern Great Plains in Washburn, North Dakota. Jenkinson covers the deep culture of the state-wide political spectrum, including an acute and thoughtful post-mortem on North Dakota Governor Art Link, and ruminations on the sense of place at Theodore Roosevelt’s national park. This is all the more pressing considering how North Dakota is experiencing a global industrial petroleum boom (as of 2013, North Dakota is the #2 producer of petroleum in the United States, this just behind Texas).

In light of this, Jenkinson also showcases artists who literally come from the North Dakota soil. Chuck Suchy is one, a farmer and rancher with roots from Bohemia and on the upper Missouri River (not too far south of Mandan, North Dakota, to be exact). As Jenkinson describes Chuck, “He’s a working farmer, which means that… He so clearly loves this place, its history, heritage, its people, its quirkiness, its muted west-[Missouri-]river landscape beauty, that he can really be called the voice of North Dakota.” Of Chuck Suchy and his family of musicians, this is true. It is Bohemia on the northern Great Plains, something that Willa Cather alluded to in her novels, and this is why Garrison Keillor continuously calls upon Chuck’s talent when The Prairie Home Companion radio show enters North Dakota.

Another story of individual North Dakotan nature comes in the form of a slightly anonymous “Mr. R” who secured staples for his family during the famous blizzard of 1966. Jenkinson is at one of his literary peaks here, remembering how Mr. R. “bundled up in all the coats, mittens, and scarves he owned,” and “silently knelt down to buckle up his overshoes” before heading out into the blizzard abyss. Quite a while went by before Mr. R. returned to his family, and when he did he revealed his cache: “a loaf of bread, a case of Hamms beer, and two cartons of cigarettes.” Jenkinson says, “It took many years for Mr. R. to live down that story.” These otherwise humorous and anecdotal tales feel honest, and Jenkinson and other public historians are increasingly turning their attention to these local stories, memoirs and histories. (See, for example, Tammy S. Gordon’s, Private History in Public: Exhibition and the Settings of Everyday Life, AltiMira Press, 2010).

A review would not be fair without critique, though. While reading Jenkinson’s essays, a reader hopes for but never gets more than a couple of essays on Great Plains Native America — they were, after all, the first North Dakotans. In addition to this, he suggests that everything non-North Dakotan is somehow inferior to North Dakota. This is odd, especially when contextualized with his love for original non-North Dakotans such as Thomas Jefferson, C.S. Lewis, Theodore Roosevelt, T.S. Eliot, Dylan Thomas, George Frideric

Handel, Meriwether Lewis & William Clark, and Henry David Thoreau (among others). These figures are central in the culture and history of the Atlantic World, the stuff that Wallace Stegner grew up with in the first half of the 20th century. Jenkinson’s ruminations on them show intellect, but they do not speak to genuine and authentic touchstones of North Dakota culture and history, or the people who have a genealogical connection with the land.

Perhaps, though, this is the theme throughout the book: Jenkinson is a North Dakota nationalist with advanced training in Western Civilization. He is a patriotic Euro-American booster for the geo-political abstraction that is North Dakota. And this is how it has to be — a love for the abstraction — since it would be logistically impossible for him to meet and love every individual North Dakotan. This, no doubt, makes a reader eager for Jenkinson and The Dakota Press to fill in the gaps with a follow-up to For the Love of North Dakota. Considering how the booming Petroleum Industrial Complex is altering the culture of North Dakota in the second decade of the 21st century, writers such as Jenkinson are all the more important. There is an infinite amount of North Dakotans and New North Dakotans throughout the state that have individual stories worth telling, and Jenkinson has the pen and vocabulary for it.

Involved in historic preservation and cultural resource management since 2002, Aaron L. Barth is a PhD candidate in history with North Dakota State University, Fargo. His focus is on Great Plains, Public, and World History. In addition to this, he is a board member with the North Dakota Humanities Council. Barth’s blogspot can be found at The Edge Of The Village.

No comments:

Post a Comment